Friday, December 21, 2012

An Experiment with Video

The skies in Elephant Butte are clear tonight. I went out with my little HandiCam and a tripod just to see what I might be able to get. Here is the result - a video showing the planet Jupiter. While very grainy, 4 of its moons may be seen, in a line tilted to the right about 30 degrees from vertical.

Friday, December 7, 2012

Water Returns to Elephant Butte Lake

In 2010, Elephant Butte Lake was a vast reservoir, used for fishing and watersports, as well as military training for diver deployment and recovery. From my campsite, the lake stretched several miles wide to the mountains on the far side.

When Texas was hit so hard by drought and wildfires, water was exported to the neighboring state and the lake level dropped substantially. Since then, it has dropped even more. When I got here in late October, there was no more lake visible, just a narrow channel that carried a trickle of water and was named the Rio Grande. Not so grand...

We were able to drive to what had been the center of the lake, over 1.5 miles into the lake bottom, where former lake bed had become flat plain.

Now, six weeks later, the flow in the Rio Grande has increased substantially and the lake is slowly filling. What used to be dry flat soil with a covering of grasses and scrub brush is now a marsh.

Slowly, the reflections that gave me such nice images to photograph are returning. Dawn is once again a spectacle worth arising to see.

When Texas was hit so hard by drought and wildfires, water was exported to the neighboring state and the lake level dropped substantially. Since then, it has dropped even more. When I got here in late October, there was no more lake visible, just a narrow channel that carried a trickle of water and was named the Rio Grande. Not so grand...

We were able to drive to what had been the center of the lake, over 1.5 miles into the lake bottom, where former lake bed had become flat plain.

Now, six weeks later, the flow in the Rio Grande has increased substantially and the lake is slowly filling. What used to be dry flat soil with a covering of grasses and scrub brush is now a marsh.

Slowly, the reflections that gave me such nice images to photograph are returning. Dawn is once again a spectacle worth arising to see.

Saturday, November 3, 2012

Kasha Katuwe Tent Rocks

Six to seven million years ago, a volcanic eruption from the Jemez volcanic field left layers of ash, pumice and tuff. Pyroclastic flows added to the layers. Today, harder cap rocks have protected, to some extent, softer rocks below, resulting in fantastic tent-shaped formations.

Trails bring visitors into the formation area.

One of the trails follows a slot canyon mere feet wide.

When the trail emerges from the slot canyon it leads hikers up a steep path to the ridge above the formations.

From there, views reveal the surrounding lands and the tops of the fantastic formations that give this area its name.

Trails bring visitors into the formation area.

One of the trails follows a slot canyon mere feet wide.

When the trail emerges from the slot canyon it leads hikers up a steep path to the ridge above the formations.

From there, views reveal the surrounding lands and the tops of the fantastic formations that give this area its name.

Thursday, September 27, 2012

Along the Rio Chama

I went for a drive the other day. A friend recommended that I take the drive to a nearby monastery, so I did. The dirt road followed the Rio Chama for much of its course. The changing leaves and the far cliffs set me up for a few nice shots.

On the way out, with the sun behind me, some of the formations became really nice.

A bit later, the skies became stormy. The sun was playing hide and seek with the clouds. When it was out, the light was a real treat.

On the way out, with the sun behind me, some of the formations became really nice.

A bit later, the skies became stormy. The sun was playing hide and seek with the clouds. When it was out, the light was a real treat.

Red rocks against a white and blue sky - gotta love those colors!

Sunday, September 23, 2012

Welcome to Abiquiu

After I left Heron Lake, I headed south for a 2 week stay at Abiquiu Lake. Abiquiu gained some notoriety from one of its residents - Georgia O'Keefe. I can't say for sure that this is right, but I understand that the photo below is of the cabin where she stayed.

The surrounding land is characterized by the iconic sandstone, shaped by wind and water, set amid high desert.

I can only imagine sitting in that cabin and watching the dramatic sunsets that have been such a rewarding aspect of my stays in New Mexico.

The surrounding land is characterized by the iconic sandstone, shaped by wind and water, set amid high desert.

I can only imagine sitting in that cabin and watching the dramatic sunsets that have been such a rewarding aspect of my stays in New Mexico.

Saturday, September 15, 2012

On The Edge

First, there was "Travels To The Edge with Art Wolfe", a PBS series in which Art Wolfe, a master photographer, is accompanied by a film crew as he goes to, and photographs, marvelous places. More recently, a knock-off of this idea, "Beyond The Edge with Peter Lik" was done. Art Wolfe tells an entertaining and informative story in each half hour segment. Peter Lik shares the challenges and frustrations involved in trying to get that "gallery shot".

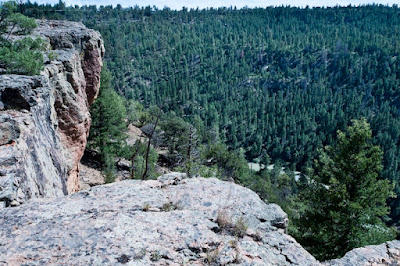

So, here is my version of "edgy" photography. I am at Heron Lake in New Mexico. The Rio Chama flows out of the dam that forms the reservoir, into a canyon 430 feet below the rim that is perhaps a half mile south of where I am sitting at this moment. I hiked to that edge yesterday.

Approaching the edge, it is a very sharp lip of hard, tight rock, tilting slightly away from the chasm.

Some great views are available of the river below and the canyon formed by it.

The area near the edge is decorated with vegetation, including wildflowers.

Looking carefully (and when you go, alone, to such places you ALWAYS need to look carefully) that solid, tight edge looks a little less secure. First, it tends to be undercut, so the rock right at the edge is resting on air.

What is really unsettling is that there are often fissures near the edge.

These fissures are being enlarged by moisture that penetrates the cracks, filling them with ice in the winter. The ice expands and pushes the crack open a tiny bit more each year. In places, these fissures can be all but invisible, marked only by a line of vegetation whose roots find moisture below the rock surface that underlies a thin film of dirt.

Some are easy to spot.

Others are harder.

With some, a faint crack here and there in the rock, and a line of trees, may be your only warning. Instinct is your friend (and no, they do not come with nice, neat red dashed lines marking them)

In places they can be deep, pronounced and unmistakeable.

Here is what it looks like BELOW that fissure.

I tried to be sure that I did not walk on the edge side of any fissures, whether subtle or obvious. In geological terms, these overhangs are about to drop into the canyon. Maybe it will happen in 10,000 years, or 100 years, or maybe tomorrow. All I know is I do not want to be standing on the edge when it decides it is time to drop.

So - why go to such places? For the view, of course.

Even the walk back on the flats can be nice.

So, here is my version of "edgy" photography. I am at Heron Lake in New Mexico. The Rio Chama flows out of the dam that forms the reservoir, into a canyon 430 feet below the rim that is perhaps a half mile south of where I am sitting at this moment. I hiked to that edge yesterday.

Approaching the edge, it is a very sharp lip of hard, tight rock, tilting slightly away from the chasm.

Some great views are available of the river below and the canyon formed by it.

The area near the edge is decorated with vegetation, including wildflowers.

Looking carefully (and when you go, alone, to such places you ALWAYS need to look carefully) that solid, tight edge looks a little less secure. First, it tends to be undercut, so the rock right at the edge is resting on air.

What is really unsettling is that there are often fissures near the edge.

These fissures are being enlarged by moisture that penetrates the cracks, filling them with ice in the winter. The ice expands and pushes the crack open a tiny bit more each year. In places, these fissures can be all but invisible, marked only by a line of vegetation whose roots find moisture below the rock surface that underlies a thin film of dirt.

Some are easy to spot.

Others are harder.

With some, a faint crack here and there in the rock, and a line of trees, may be your only warning. Instinct is your friend (and no, they do not come with nice, neat red dashed lines marking them)

In places they can be deep, pronounced and unmistakeable.

Here is what it looks like BELOW that fissure.

I tried to be sure that I did not walk on the edge side of any fissures, whether subtle or obvious. In geological terms, these overhangs are about to drop into the canyon. Maybe it will happen in 10,000 years, or 100 years, or maybe tomorrow. All I know is I do not want to be standing on the edge when it decides it is time to drop.

So - why go to such places? For the view, of course.

Even the walk back on the flats can be nice.

Adios Colorado

She treated me nicely, but it is time to ease on down into New Mexico. So, here are a few parting thoughts and images.

Driving from Ouray to Silverton was a pretty amazing experience. The road is steep, two lane, winding, has no shoulder or edge protection and is a LOOOOONG way down. From the cab, I could see nothing but air beyond the edge of pavement. I am very glad I did it, but I don't think I will plan that route again.

After Silverton, I wound up in Durango. I had a time constraint while there so I did not get to see the steam train that goes from Durango to Silverton. Perhaps I will manage that another time. I DID get to see the Cumbres and Toltec train. It does a sightseeing run from Chama, NM up into Colorado, then back. I caught it right at the State line.

After getting a few minor vehicle problems taken care of, I went exploring. A Forest Service road took me high into the mountains. There, I got to see many of the trees that gave Aspen, CO its name. They were crowned in autumn gold, held up by their white legs.

Sweet.

Driving from Ouray to Silverton was a pretty amazing experience. The road is steep, two lane, winding, has no shoulder or edge protection and is a LOOOOONG way down. From the cab, I could see nothing but air beyond the edge of pavement. I am very glad I did it, but I don't think I will plan that route again.

After Silverton, I wound up in Durango. I had a time constraint while there so I did not get to see the steam train that goes from Durango to Silverton. Perhaps I will manage that another time. I DID get to see the Cumbres and Toltec train. It does a sightseeing run from Chama, NM up into Colorado, then back. I caught it right at the State line.

After getting a few minor vehicle problems taken care of, I went exploring. A Forest Service road took me high into the mountains. There, I got to see many of the trees that gave Aspen, CO its name. They were crowned in autumn gold, held up by their white legs.

Sweet.

Thursday, September 6, 2012

Colorado Gold

I spent two days in the western range in Colorado. On one of those days I drove up to Cottonwood Pass, over 12,000 feet high. Part way there, the road led through an arid, relatively flat valley. Perched on a hill overlooking that valley was a beautiful hawk.

He only allowed me a few minutes of looking before he took flight.

He did grace me with a fly-over as he floated toward the hills in the distance.

Heading down the hill, the sun lit up leaves that were beginning the Autumn change.

Even marsh grasses were turning gold.

He only allowed me a few minutes of looking before he took flight.

He did grace me with a fly-over as he floated toward the hills in the distance.

Heading down the hill, the sun lit up leaves that were beginning the Autumn change.

Even marsh grasses were turning gold.

The Black Canyon of the Gunnison

Wow.

I have seen the vastness ot the Grand Canyon, the depth of Hells Canyon, the narrowness of Antelope Canyon, the vertical walls of Canyon de Chelle, but nothing has compared with this. At 2300 feet deep, the Black Canyon is not as deep as the Grand Canyon or Hells Canyon but with them, the bottom is waaaay over there. At the Black Canyon, it is straight down below you. Canyon de Chelle has vertical walls, but they enfold a flat plain that has been farmed for centuries before Europeans found it.

The Black Canyon took my breath away. The far side is perhaps a thousand feet from you as you lean over and look down nearly half a mile to the river squeezing its way between boulders that choke its path.

A few miles to the north and south the land is underlain by soft shale. Millenia ago, the Gunnison River began its cutting in this path. As it encountered a metamorphic rock strata, some of the hardest rock known, it was locked into its bed. As the land rose, the only direction it had was down, and so it began to cut its way, deeper and deeper into an incredibly hard surface.

No Native Americans called this rugged Canyon home. There is no sign that they even had trails through it.

The overlooks place you right at the edge, with nothing but air between you and the river far below.

Seams allowed intrusions of even harder rock (pegmatite, if I remember right). The lighter colored material forms stripes in the wall. The far wall in this photo is named the Painted Wall, and rises 2300 uninterrupted feet from the Gunnison River.

Its name comes from its depth and verticality. Sunlight almost never reaches the bottom in many places and except at the few times when the sun falls upon the walls, the Canyon has a dark, almost brooding feel.

Wow

I have seen the vastness ot the Grand Canyon, the depth of Hells Canyon, the narrowness of Antelope Canyon, the vertical walls of Canyon de Chelle, but nothing has compared with this. At 2300 feet deep, the Black Canyon is not as deep as the Grand Canyon or Hells Canyon but with them, the bottom is waaaay over there. At the Black Canyon, it is straight down below you. Canyon de Chelle has vertical walls, but they enfold a flat plain that has been farmed for centuries before Europeans found it.

The Black Canyon took my breath away. The far side is perhaps a thousand feet from you as you lean over and look down nearly half a mile to the river squeezing its way between boulders that choke its path.

A few miles to the north and south the land is underlain by soft shale. Millenia ago, the Gunnison River began its cutting in this path. As it encountered a metamorphic rock strata, some of the hardest rock known, it was locked into its bed. As the land rose, the only direction it had was down, and so it began to cut its way, deeper and deeper into an incredibly hard surface.

No Native Americans called this rugged Canyon home. There is no sign that they even had trails through it.

The overlooks place you right at the edge, with nothing but air between you and the river far below.

Seams allowed intrusions of even harder rock (pegmatite, if I remember right). The lighter colored material forms stripes in the wall. The far wall in this photo is named the Painted Wall, and rises 2300 uninterrupted feet from the Gunnison River.

Its name comes from its depth and verticality. Sunlight almost never reaches the bottom in many places and except at the few times when the sun falls upon the walls, the Canyon has a dark, almost brooding feel.

Wow

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)